A Site About Dead Musicians and How They Got That Way

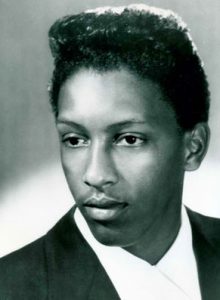

Jesse Belvin: Age 27 | Cause Of Death: CAR CRASH / MYSTERIOUS CIRCUMSTANCES

(b. 15 December 1932, San Antonio, Texas, USA, d. 6 February 1960)

Earth Angel, a collaboration with two fellow conscripts, was recorded successfully by The Penguins, while Belvin enjoyed a major hit in his own right with Goodnight My Love, a haunting, romantic ballad adopted by disc jockey Alan Freed as the closing theme to his highly-influential radio show. In 1958 Belvin formed a vocal quintet, The Shields, to record for Dot Records the national Top 20 hit, You Cheated. That same year the singer was signed to RCA Records, who harboured plans to shape him in the mould of Nat King Cole and Billy Eckstine. Further hits, including Funny and Guess Who —the latter of which was written by his wife and manager Jo Ann—offered a cool, accomplished vocal style suggestive of a lengthy career, but Belvin died, along with his wife, following a car crash in February 1960.

Less than three weeks before the first anniversary of the plane crash that killed Buddy Holly and Ritchie Valens, and some 32 years before a presidential candidate made it one of America’s most famous small towns, Hope, Arkansas was the site of a horrific car accident. Though very few fans of modern rock and pop music are aware of it, the crash snuffed out the life and career of Jesse Belvin, a major figure in the fusion of black soul and white folk music.

It is strange that Belvin’s passing is rarely noted or even mentioned in written histories of American music. He co-wrote one of the biggest hits of the 1950s — “Earth Angel,” a hit for The Penguins in 1955 — and his recording of “Goodnight My Love” was used by Dick Clark as the closing theme for “American Bandstand” for several years.

Belvin was a golden-voiced crooner who could be a Nat King Cole clone on Tuesday, singing “Guess Who?” and “Old Man River,” only to out-Elvis Presley himself on Wednesday, with tunes like “By My Side” and “Just To Say Hello.”

In fact, it was that very talent for his emulation of Presley and Little Richard that caused RCA Records to sign Belvin and begin a unique promotion in 1959.

It would be a few years before the civil rights movement built up momentum, and RCA wanted badly to tap into the segregated South, by offering a “Black Elvis.” This was ironic, indeed; early promotional material for Presley often called him “The White Soul Singerm” or “A White Little Richard.”

The fatal car crash came less than four hours after Belvin had performed the first integrated concert — that is, to an integrated audience — in Little Rock. It had been an ugly scene: White supremacists managed to halt the show twice, shouting racial epithets and urging the white teenagers in attendance to leave at once.

There had been at least six death threats on Belvin. So, speeding away from Arkansas was truly a relief, and a cause for celebration.

Belvin’s wife, JoAnn, died from her injuries at the Hope Hospital, while his driver — like Jesse — died at the scene.

As word reached the black community in Belvin’s hometown, Los Angeles, there were immediately rumors of foul play.

One of the first state troopers on the accident scene stated that both of the rear tires on Belvin’s black cadillac had been “obviously tampered with.” He gave no more details, causing even more speculation. The fact that Belvin had phoned his mother twice in the last three days, every time telling her about the hostile receptions he received, made suspicions stronger: He rarely called home from the road, and never more than once a month.

Belvin’s two children were left orphans, until their paternal grandmother agreed to assume legal custody.

In passing, Belvin left behind a legacy of brilliant songwriting as well as a plethora of doubts and confusion. It seems unlikely his story would go untold until the end of the century, even as Holly and Valens were resurrected and immortalized as Rock Gods. Yet, of 500 people surveyed, only one knew who Belvin was, while just seven thought they had heard his name before.

The scorched earth on the highway at Hope was still visible in 1980, leaving us with a sad and painful vacuum, close to the heart of rock and roll.

It is obvious Belvin has been relegated to the end of the rock legend line … but the quest to make his story known is ever-thriving. We only hope it will one day be told. ~Copyright 1992, 1998 ~ by Eric Lenaburg

Fuller Up The Dead Musicians Directory

Jesse Lorenzo Belvin

Jesse Belvin

Age: 27

Died: February 06, 1960

Cause Of Death: CAR CRASH / MYSTERIOUS CIRCUMSTANCES

Obituary

By Eric Lenaburg

Less than three weeks before the first anniversary of the plane crash that killed Buddy Holly and Ritchie Valens, and some 32 years before a presidential candidate made it one of America’s most famous small towns, Hope, Arkansas was the site of a horrific car accident. Though very few fans of modern rock and pop music are aware of it, the crash snuffed out the life and career of Jesse Belvin, a major figure in the fusion of black soul and white folk music.

It is strange that Belvin’s passing is rarely noted or even mentioned in written histories of American music. He co-wrote one of the biggest hits of the 1950s — “Earth Angel,” a hit for The Penguins in 1955 — and his recording of “Goodnight My Love” was used by Dick Clark as the closing theme for “American Bandstand” for several years.

Belvin was a golden-voiced crooner who could be a Nat King Cole clone on Tuesday, singing “Guess Who?” and “Old Man River,” only to out-Elvis Presley himself on Wednesday, with tunes like “By My Side” and “Just To Say Hello.”

In fact, it was that very talent for his emulation of Presley and Little Richard that caused RCA Records to sign Belvin and begin a unique promotion in 1959.

It would be a few years before the civil rights movement built up momentum, and RCA wanted badly to tap into the segregated South, by offering a “Black Elvis.” This was ironic, indeed; early promotional material for Presley often called him “The White Soul Singer” or “A White Little Richard.”

The fatal car crash came less than four hours after Belvin had performed the first integrated concert — that is, to an integrated audience — in Little Rock. It had been an ugly scene: White supremacists managed to halt the show twice, shouting racial epithets and urging the white teenagers in attendance to leave at once.

There had been at least six death threats on Belvin. So, speeding away from Arkansas was truly a relief, and a cause for celebration.

“It was eerily reminiscent of a 1956 integrated concert in Alabama, when the legendary Nat “King” Cole returned to his own hometown for a concert. Anticipating a warm reception — after all, by this time Cole had reached iconic status, had his own television show, and was seemingly beloved by white audiences — and he was returning to the very roots of his youth. “Yet, less than 20 minutes into the set, Cole and his band were quite literally chased from the stage and beaten. Cole never did come to grips with that horrible night, and vowed never to return to the stage in Alabama – a promise he kept right up until his tragic death from Cancer.”

Belvin’s wife, JoAnn, died from her injuries at the Hope Hospital, while his driver — like Jesse — died at the scene.

As word reached the black community in Belvin’s hometown, Los Angeles, there were immediately rumors of foul play.

One of the first state troopers on the accident scene stated that both of the rear tires on Belvin’s black Cadillac had been “obviously tampered with.” He gave no more details, causing even more speculation. The fact that Belvin had phoned his mother twice in the last three days, every time telling her about the hostile receptions he received, made suspicions stronger: He rarely called home from the road, and never more than once a month.

Belvin’s two children were left orphans, until their paternal grandmother agreed to assume legal custody.

In passing, Belvin left behind a legacy of brilliant songwriting as well as a plethora of doubts and confusion. It seems unlikely his story would go untold until the end of the century, even as Holly and Valens were resurrected and immortalized as Rock Gods. Yet, of 500 people surveyed, only one knew who Belvin was, while just seven thought they had heard his name before.

The scorched earth on the highway at Hope was still visible in 1980, leaving us with a sad and painful vacuum, close to the heart of rock and roll.

It is obvious Belvin has been relegated to the end of the rock legend line … but the quest to make his story known is ever-thriving. We only hope it will one day be told.

Copyright 2003 by Eric Lenaburg

Biography

(b. 15 December 1932, San Antonio, Texas, USA, d. 6 February 1960)

Raised in Los Angeles, Belvin became a part of the city’s flourishing R&B scene while in his teens. He was featured on ‘All The Wine Is Gone’, a 1950 single by Big Jay McNeely, but his career was then interrupted by a spell in the US Army. ‘Earth Angel’, a collaboration with two fellow conscripts, was recorded successfully by the Penguins , while Belvin enjoyed a major hit in his own right with ‘Goodnight My Love’, a haunting, romantic ballad adopted by disc jockey Alan Freed as the closing theme to his highly influential radio show. He also recorded with fellow songwriter Marvin Phillips as Jesse & Marvin, achieving a Top 10 R&B hit in 1953 with ‘Dream Girl’. In 1958 Belvin formed a vocal quintet, the Shields, to record for Dot Records the national Top 20 hit ‘You Cheated’. That same year the singer was signed to RCA Records, who harbored plans to shape him in the mould of Nat ‘King’ Cole and Billy Eckstine . Further hits, including ‘Funny’ and ‘Guess Who’ – the latter of which was written by his wife and manager Jo Ann – offered a cool, accomplished vocal style suggestive of a lengthy career, but Belvin died, along with his wife, following a car crash in February 1960.

Encyclopedia of Popular Music Copyright Muze UK Ltd. 1989 – 1998